MISTLETOE

The maligned and misunderstood step-sister of holly, poinsettia, and Christmas trees!

As a child, I fondly remember collecting wild mistletoe from the pine and oak woodlands of my home in California’s Sierra Nevada foothills. I would wrap the mistletoe sprigs with bright red ribbons and offer them for sale to my neighbors at Christmas time.

Forest greenery of all sorts has long been associated with the holiday season. Fragrant conifer boughs, red-berried holly branches and mistletoe sprigs have all served to brighten our homes during the long, dark nights of winter. Their green branches remind us that life, though dormant, will return as surely as spring.

Among the plants most associated with the yuletide season, Mistletoe is nonetheless often maligned and misunderstood. So, let’s delve into some facts about this fascinating group of plants.

Quick Facts About Mistletoe Species

- Many ancient cultures used mistletoes in their rituals, festivals, and as herbal remedies.

- The Yuletide tradition of kissing under the mistletoe was popularized in Victorian-era England.

- There are 1,000’s of species of mistletoes spread across three plant families.

- Mistletoes live as ‘hemiparasites, taking some, but not all, of their nutrition from their hosts.

- They live on the branches of a wide variety of deciduous and evergreen trees.

- Mistletoes play an important role in the lives of many species of insects, birds, and mammals.

- Ingesting mistletoe is not as deadly as is often rumored, though it will certainly cause gastrointestinal distress and should be kept away from pets and children.

- And drumroll, please…Mistletoe is Oklahoma’s state Floral Emblem!

What is Mistletoe?

Mistletoes share the common features of being arboreal, epiphytic plants that are hemiparasites of the branches of the trees they live upon. ‘Hemi’, or half, meaning that while they certainly rely on their host for much of their water and nutrients, they do have green leaves and are thus able to gather some of their own energy from the sun, in contrast to fully parasitic, chlorophyll-lacking plants such as red-tinted Snow Plants and Pinedrops.

Mistletoe Diversity

You can be forgiven if you assume that there’s just one type of mistletoe; the species we decorate our doorways with at Christmas. In reality,

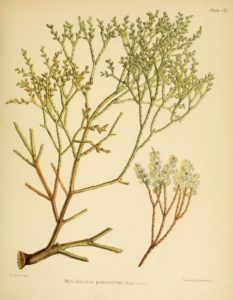

In reality, mistletoes are taxonomically diverse. The word is a catch-all phrase that refers to any of 1000s of species within 3 families; the Misodendraceae (8-ish species restricted to Chile and Argentina), the Loranthaceae (a widespread family of 1,000+ species so-called ‘showy mistletoes for their pretty bird-pollinated flowers), and the Santalaceae, or Sandalwood family.

In this story, we will focus our attention primarily on this third family which includes the familiar North American and European mistletoe species within its 1,000 or so members.

Which is the Yuletide Mistletoe?

Just one species, the European Mistletoe, Viscum album, has played the starring role in most of the traditions, folklore, and mythology associated with winter holidays, as it is the only mistletoe native to much of Europe.

In North America, the mistletoe most often seen in Christmas displays and used for Yuletide kissing belongs to the genus Phoradendron, a group that actually boasts several hundred species throughout the Americas, with its center of diversity being in the Amazon rainforest!

Mistletoes: Often Maligned and Misunderstood

As plant parasites, mistletoes have a largely undeserved reputation as killers of forests and destroyers of trees. But just as in any commensal relationship between species (including humans!) the reality is much more subtle than it at first appears.

Indeed, some types do have a more deleterious effect on their hosts. A group of species known as ‘dwarf’ mistletoes, like Arceuthobium, tend to be much more damaging to trees since their photosynthesizing leaves are drastically reduced compared to the ‘leafy’ mistletoes. These dwarves parasitize pine and cypress trees across the Americas, Eurasia, and Africa.

The Dwarf Mistletoe has smaller fruits than the leafy mistletoes, so instead of relying on birds to eat and disperse its seeds, it distributes itself with a different mechanism – exploding berries that shoot each rice grain-sized seed away from itself at up to 50 mph!

Dwarf Mistletoe

The more attractive-looking and familiar ‘leafy’ mistletoes tend to cause less damage though some mistletoe-infected trees do have a shorter lifespan than their healthier neighbors. But their dead snags provide important nesting sites for woodpeckers and many other cavity-nesting birds and mammals, increasing the overall diversity, stability, and health of the entire ecosystem.

Mistletoes, like bark beetles, often have a truce with the trees they infect, causing the death of only those trees already weakened by disease, drought, or old age.

Perhaps you’ve never examined a mistletoe closely, only glancing at their dense clumps in oaks or pines with mild disdain assuming they are deadly parasites. As an evergreen, mistletoe is particularly apparent in winter when growing in deciduous trees that have lost their leaves.

But look again and you may appreciate their simplicity of form and their plump white berries. I find the European Mistletoe to be especially beautiful with the perfectly dichotomously branching pattern of its stems.

Birds and Mistletoes

Mistletoes serve important roles in the ecosystems they inhabit as both food, mating, and nesting sites for a variety of insects, mammals, and birds.

Many birds rely on the abundant crops of mistletoe berries as part of their diets. In Eurasia, the berries of European Mistletoe are enjoyed by such birds as Mistle Thrushes, and Fieldfares, and Blackcap.

Eurasian Blackcap

In North America, the Phainopepla uses the plant as its main food source, especially in winter. In the Sonoran Desert, where the parasite grows on acacia and mesquite trees, Phainopeplas spend a lot of time gulping down mistletoe berries. The Phainopepla may eat over 1,000 juicy mistletoe berries in one day, enough to provide the bird with all the water they need!

Phainopepla

Birds not only eat the fruits of mistletoe but serve as vital seed dispersers since the ingested seeds are often deposited on tree branches where they can sprout into new plants.

Other mistletoe berry eaters include grouse, mourning doves, bluebirds, evening grosbeaks, robins, and pigeons, according to the USGS research ecologist, Todd Esque, who took the photo below of a Mountain Bluebird among mistletoe branches.

Mountain Bluebird / by Todd Esque, USGS.

Many species of trees have a love/hate relationship with the mistletoes that infect their branches. For example, juniper trees spread a higher percentage of their berries (the same ones used in making gin by the way!) when hosting some mistletoe clumps because both mistletoe and juniper attract berry-eating birds who serve to ingest and spread the seeds of both plant species.

Witches’ Brooms

Trees infected with mistletoes often form densely tangled deformities of branches known as witches’ brooms that can provide safe nesting and roosting sites for birds including the Spotted Owl and Marbled Murrelet in the Pacific Northwest of the U.S. In fact, researchers in northeastern Oregon (near where I live) found that 64% of all Cooper’s hawk nests were in mistletoe.

Witches’ Broom

Mammals and Mistletoe

Many mammals take advantage of abundant crops of mistletoe berries, especially in the wintertime when other foods are scarce. Elk, deer, squirrels, chipmunks, and even porcupines enjoy the juicy white fruits which help sustain them until spring arrives.

A variety of squirrels including red squirrels, flying squirrels and Abert’s squirrels also use dense witches’ brooms for cover and nesting sites.

A clump of mistletoe with a squirrel nest inside

Butterflies and Mistletoe

As you may know, many butterflies and moths rely on specific species of plants to lay their eggs on and these plants also serve as an important food source for the larvae.

Three species of hairstreak butterflies in the United States rely on mistletoes. One example is the Great Purple Hairstreak Butterfly, pictured below, that drinks the floral nectar of the American Mistletoe.

This beautiful butterfly also courts upon and lays its eggs on the mistletoe, where the resulting caterpillars thrive exclusively on a mistletoe diet.

Great Purple Hairstreak Butterfly

Mistletoe’s Symbolism

Mistletoe has played symbolic roles in numerous cultures around the world. In ancient Greek mythology, the hero Aeneas used mistletoe to reach the underworld. The Greek goddess Artemis (patron of the city of Ephesus which I was lucky to visit once) wore a crown of mistletoe as an emblem of fertility and immortality.

The plump, white berries of mistletoe reminded some cultures of human semen, such as the Celts, who viewed them as the sperm of Taranis, and the Greeks referred to the plant as oak sperm

The Romans associated mistletoe with peace, love, and understanding and hung it over doorways to protect the home, and this tradition was also part of the Saturnalia, a midwinter’s festival in honor of the god Saturn.

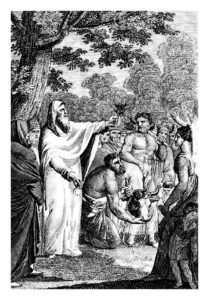

Druid Ritual of Oak and Mistletoe

Pliny the Elder wrote in the first century of mistletoe traditions of the Celts in his encyclopedic series, Natural History. He recounts the Ritual of Oak and Mistletoe in which white-clad druids climbed a sacred oak, cut down the mistletoe growing on it, sacrificed two white bulls, and used the mistletoe to make an elixir to cure infertility and the effects of poison.

The modern tradition of kissing under the mistletoe is said to have had its roots in 16th century England.

Learn More About Mistletoe

The more I researched mistletoe, the more fascinated I became and realized that instead of writing a book, I’d share these resources with you!

- Not Just for Kissing: Mistletoe and Birds, Bees, and Other Beasts

- Mistletoe: What’s It to the Birds?

- Biodiversity value of mistletoe

- Mistletoe Birds

- How Mistletoe Became Everyone’s Favorite Parasite

- Mistletoe seed dispersal

- Many Birds Rely on Mistletoe

- Various Articles from ScienceDirect on Mistletoe

Happy Yuletide Season!

In wrapping up this story, I hope that you learned some surprising facts about mistletoes and thus gained a greater appreciation for their history, ecological significance and subtle beauty. And here’s hoping that you have a loved one to kiss under the mistletoe this season!