Stories about the flora and fauna I observed during my first trip to Costa Rica in 2019 (I’ve since returned 3 times!)

In Search of Quetzals

I was treated to a morning birdwatching in the field with guide Jorge Serrano Salazar from Paraiso Quetzal Lodge to search out a very special bird, the iconic Resplendent Quetzal. The lodge is located south of Cartago at 8,500 feet elevation in the cloud forest ecosystem, sandwiched between two large national parks, Los Quetzales and Tapanti.

The lodge works with a network of over 20 local farming families who help to protect the quetzal and who also alert the guides when some birds have been found feeding in their property’s avocado trees. The quetzal’s diet consists of up to 70% avocado fruit from several species that live in Central America, supplemented by other fruits, berries, insects and small amphibians.

After filling up on some hot coffee and cookies, Jorge and I, along with a nice couple from Germany, set out down the nearby Pan-American Highway and parked at one of the ranching family’s gates.

After a short stroll, we almost immediately spied both a male and female quetzal in some avocado trees right above our heads. The birds were so relaxed that I even got to spend a few minutes sketching a male, who sat quietly for me.

Since nesting season had just ended, none of the males had their festive 2-foot-long tail feathers, which are usually lost during this time, but no matter. The birds were still impossibly beautiful with their brightly iridescent green and blue bodies and warm red chests.

Once the quetzals had flown, we turned our attention to some nearby trees festooned with mosses, lichens, and bromeliads. Among their beefy branches we viewed a wide assortment of colorful neotropical species including the collared redstart, flame-colored tanager, mountain thrush, yellow-thighed finch, spot-crowned woodcreeper, long-tailed silky-flycatcher, ruddy-capped nightingale thrush, ochraceous wren, white-breasted wood wren, purple-throated mountain gem, and red-faced spinetail. The birds were busily foraging on various fruits and insects in the trees and paid us no mind.

All too soon, it was time to return to the lodge where I took advantage of the rare clear blue sky to continue exploring the grounds and trails until a thunderstorm threatened and I retreated to the fireplace-warmed restaurant to enjoy a hot drink. What a day!

LEARN MORE ABOUT PARAISO QUETZAL LODGE

A Birding Big Day

I challenged myself to my own artist’s version of a Birding Big Day on August 19th at Rancho Naturalista in Costa Rica. Watch the video slideshow below to see samples of my 15 pages of sketches I completed during the 12 hours of daylight.

Watch the Video Compilation!

**READ THE WHOLE BLOG POST ABOUT MY BIG DAY HERE**

Frogs, Fabulous Frogs

When one conjures up images of rainforest frogs, the Red-eyed Leaf Frog might come to mind first. Like the Keel-billed Toucan, this frog has been seen so often in advertising, merchandise and cartoons that you’d hardly believe it was real. But indeed, it is a common and widespread species in Central American rainforests. Like other members of the Hylidae, or tree frog family, it has unique fingers and toes whose ends are expanded into adhesive disks that act as suction cups.

Once, I was lucky to see mating pairs of these frogs in Honduras as they were precariously balanced on a stem of a banana plant that was hanging over a small pond.

Red-eyed Leaf Frogs

Frogs I’ve Met in Costa Rica

The Red-eyed Leaf Frog, Agalychnis callidryas, is just one of over 147 species of frogs and toads that have been identified in Costa Rica, and there are likely many more. They range in appearance from miniscule Dink Frogs no larger than your pinkie fingernail to 3-pound Cane Toads. Some species are familiar to most, like the brightly patterned Red-eyed Leaf Frog. Others are known only to those who brave the heat and humidity of a lowland rainforest and look carefully on the undersides of leaves, amongst the leaf litter, and in the axils of epiphytic bromeliads.

Rainforests are a great place to see frogs, and amphibians in general, thanks not only to their rich species diversity but also since the perennially moist and humid climate allows them the freedom to occupy more habitats without fear of desiccation. Unlike northern hemisphere species that are tied to aquatic habitats because their skin must be moist to absorb oxygen, frogs living closer to the equator are freed to live anywhere, even in trees.

Below is a sampling of the frogs I’ve met thus far in Costa Rica.

Smoky Jungle Frog

The Smoky Jungle Frog, Leptodactylus savagei, is the largest frog in Costa Rica, as you might guess from the photo below, and is second only in size to the Marine Toad, reaching 6 inches long. They are widespread in Central America and northern South America, being found in a range of habitats and elevations.

We found this specimen sitting on the front lawn of the birdwatching lodge I was staying at, Rancho Naturalista. I picked it up to move it to a safer spot, not knowing that they apparently can secrete a very irritating toxin to ward off predators. Apparently, it didn’t consider me a threat but did indeed immediately jump out of my grasp and hopped at lightning speed across the lawn and into the forest, from where we often hear him calling at night. The species is also known for emitting a loud ‘scream’ when threatened, which unfortunately I was not lucky enough to experience.

According to my research, it apparently eats just about anything; including other frogs, birds, chicks, snakes, crabs, crayfish, invertebrates, and is supposedly the only frog known to eat scorpions!

I loved the beautiful coloration of this species, especially its copper-colored eyes and bronze-tinged sides.

Crowned Tree Frog

This Crowned Tree Frog, Anotheca spinosa, is valiantly guarding her tadpoles which she was raising inside the protected nursery site of a bamboo stem. This frog is quite unique, being the only species in its genus, and sporting a bony crown of knobs and spines on top of its head. Like poison dart frogs, the female nourishes the voracious tadpoles with a diet of unfertilized eggs laid directly in the water. Yum!

Below is a short video clip of a crowned tree frog I found that was incubating her eggs in a cut off bamboo stalk. Although I have walked by this stalk many times, I’ve only been lucky enough once to see the female perched on its edge, and thankfully I had my camera with me!

Reticulated Glass Frog

We were lucky to spot a Reticulated Glass Frog, Hyalinobatrachium valerioi, during a hike through a patch of lowland rainforest on the Atlantic side of Costa Rica. The frog was on the underside of a leaf that was overhanging a small creek. The species always places their eggs masses here so that when the tadpoles emerge from the egg, they simply drop into the creek. How ingenious!

In this species, it is the male who does the duty of watching over the eggs, day and night, to protect them from parasitic flies and other insects, and keep them hydrated by moistening them with water released from his bladder. Notice the egg-like pattern of spots on his back that may serve to fool insects into thinking he’s just another egg mass, thus luring the predators close enough to eat them!

Its small, transparent body perfectly matched the color of the leaf and we could see through the frog’s delicate skin to its skeleton and internal organs.

Reticulated Glass Frog

The Brilliant Forest Frog

The Brilliant Forest Frog, Rana warszewitschii, not to be confused with the Splendid Leaf Frog (though they’re all brilliant and splendid in my book!) is commonly seen since it’s diurnal and ground-dwelling. Folks see it, as I did, among trail-side leaf litter, though it’s mottled coloration aptly camouflages it if it doesn’t jump out of your way, as it did on a recent hike at Arenal Volcano National Park.

Like other ‘true frogs’ in the Ranidae family, it has a pair of ridges along its back and also long, muscular legs for long-distance jumping. When it does jump, it readily displays bright red and yellow bands of color that may serve to startle would-be predators as it jumps out of harm’s way. You can see a couple of the yellow spots in the photo below.

Brilliant Forest Frog

Poison Dart Frogs

All poison dart frogs belong to the family Dendrobatidae, and all 187+ species reside in the humid lowland rainforests of Central and South America, from Nicaragua to Brazil.

Each species is easy to recognize by its unique and beautiful color pattern which signals to potential predators the toxicity of the alkaloid poisons sequestered in granular skin glands. Frogs develop the poisons from their diet of spiders, ants, termites, centipedes, and beetles, but it is unclear whether the poison originates from their prey, or from the diet of the prey items themselves. Interestingly, captive frogs do not have the poison, and some species can easily be raised in captivity and are popular as pets.

Dart frogs have always been on my ‘target list’ of tropical species to see, and were one of the reasons I wanted to visit Costa Rica. I had imagined that they would be larger, but once I finally saw one, I was surprised that it was only about as big as my thumb. Once I had honed my ‘search image’ for something that small, I began to spot more.

This is the Strawberry Poison Dart Frog, Oophaga pumilio, also known as the Blue Jeans Frog for obvious reasons. This species of poison dart frog is common, widespread, and often seen due to its diurnal nature. We saw several at a time along the trails of Selvaverde Lodge and other locations within its range on the eastern side of Costa Rica.

Once seen, they are easy to observe because they don’t hop away like a ‘normal’ frog. Their short, stubby legs only allow them to amble slowly and awkwardly across the forest floor. They are also easier to see than some other frog species in that they are more terrestrial. The males like the one in this photo will generally ascend only as far as a log or small plant, from which they vocalize their territorial and courtship calls.

Males of the Strawberry Dart Frog engage in epic wrestling matches to win territories and gain the favor of females. Once a female has chosen her preferred mate, he leads her to a moist site on the forest floor where he will fertilize a small clutch of about 10 eggs. The reason for such a small clutch soon becomes apparent.

Once the eggs hatch into tadpoles they are carried by the female to a nearby bromeliad plant and there she carefully places each tadpole in a separate leaf axil. Thus, each tadpole resides in its own personal swimming pool nursery and there it resides for 40 days or so as it matures. Each day, the female will return to the bromeliad and nourish each tadpole with an unfertilized egg she deposits for it to dine on. So you can imagine how much time and effort the female dedicates and that’s why she only raises a small number of young at once.

Christine with a Strawberry Poison Dart Frog

Cane Toad

Like most species in the toad family, Bufonidae, the Cane Toad, Bufo marinus, is a short-limbed, stocky frog with warty skin. It is one of the world’s largest toads, weighing up to 3 pounds! It is recognized by both its prominent cranial crests and the enormous parotid glands located behind its eardrum that secrete copious amounts of a milky-white toxin when threatened by would-be predators.

It is common and widespread throughout its native range in Central America but has expanded farther north and south as well as becoming an ecological disaster in Australia where it was introduced in 1935 in the hopes that it would control a crop pest. No such luck.

As a voracious predator with a high reproduction rate, deadly toxicity, and ability to live in human degraded habitats, the Cane Toad, has become a much hated and feared species. If you come across one of these guys, commonly encountered at night among building with lights that attract insect prey, do avoid handling them. I spotted this big guy below at the Monteverde Cloud Forest Preserve.

Cane Toad

Honduran White Tent Bats

We observed these cute little white bats roosting under a palm leaf!

![]()

A Morning Hike at Rancho Naturalista

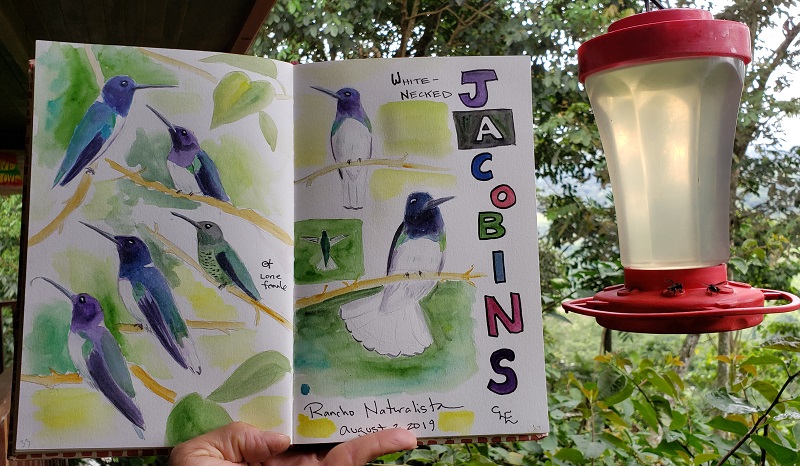

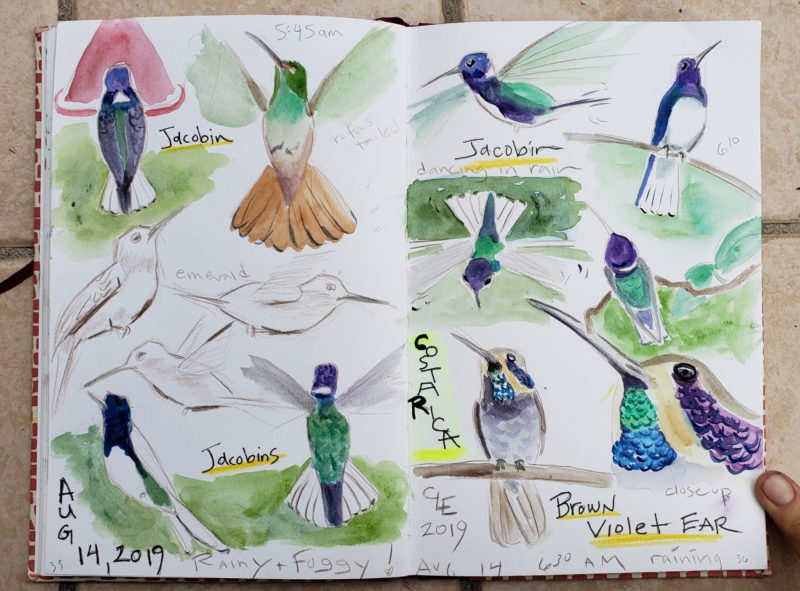

Our day started at dawn (as they tend to at birdwatching lodges!) on the balcony, where guests fill their mugs with a hearty variety of local coffee. We were instantly treated to a plethora of hummingbirds including violet sabrewings, violet-crowned woodnymphs, and white-necked jacobins, all vying for spaces at the nectar feeders.

My sketches of White-necked Jacobins at the feeders

Below the balcony, a variegated squirrel and a family of agoutis were busy stealing ripe bananas from the fruit feeders. Nearby, a Montezuma oropendola adult was feeding a demanding but nearly-grown fledgling. Looking out across the valley, we could see the slopes of Turrialba Volcano, its peak shrouded in mist.

Once my caffeine fix was satisfied, I took my first morning walk to explore the property, guided by Chon; the lodge’s ranch foreman. As we passed through the old guava tree plantation, he pointed out a patch of wild raspberries and picked some for me to try; surprisingly sweet!

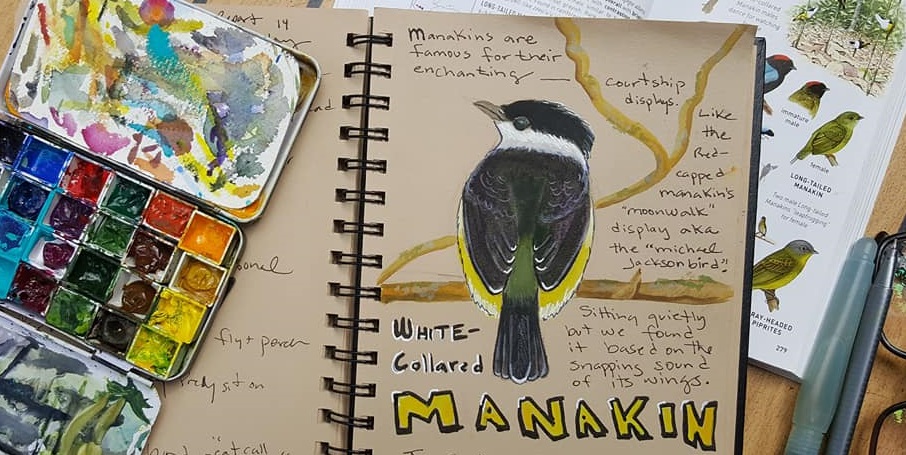

The voices of many birds accompanied us on our hike including trogons, toucans, parrots, oropendolas, chachalacas, brown jays, aracaris, woodpeckers, and others I could not identify. I heard a white-collared manakin snapping its wings as if demanding breakfast from an inattentive waiter.

Inside the shady forest, beautifully delicate glass-winged butterflies and a blue morpho butterfly flitted above us in the filtered sunlight. Dozens of armadillo dens as well as a few similar-looking motmot burrows, lined the banks of the forest trail. A 3-foot-long green parrot snake was resting on a nearby horizontal branch, blending in perfectly with its surroundings. I couldn’t resist touching the smooth skin of its tail!

We saw three species of small, intricately patterned brown frogs during our 3-hour hike; also perfectly camouflaged against the brown earth save for the fact that they hopped away from the danger of our footsteps. The trail meandered up and up, past colorful heliconias and other fragrant wildflowers. A fierce-looking tarantula hawk flew past, searching no doubt for a spider to capture and lay its eggs in! We finally reached el mirador; the lookout point, with its fantastic view of the valley and villages below.

Late each afternoon, just before sunset, a special event happens that is not to be missed; hummingbirds taking their daily dip in the creek. Here, at the hummingbird pools, one can see many shy forest species of hummers that don’t normally visit the lodge’s balcony feeders, including the purple-crowned fairy, white-tipped sicklebill, band-tailed barbthroat, stripe-throated hermit, and the bronze-tailed plumeleteer.

Returning to the lodge’s balcony for lunch we noticed some white-necked jacobin hummingbirds, with their blindingly white chests; who it seems love to celebrate the near daily afternoon showers by fanning their tails and doing a little dance on a branch in the rain.

Hummingbird sketches by Christine Elder

It’s been an amazing day here at Rancho Naturalista, the first of many I hope to enjoy during my 5-week stay, in which I’ll be creating and sharing lots of sketches and paintings inspired by this incredible corner of Costa Rica. Join me here and I’ll take you out for a hike or we can do some nature sketching! Rancho Naturalista is located a few hours drive south east of the capital city of San Jose, near the town of Turrialba.

Learn more about Rancho Naturalista on their WEBSITE.

Neotropical Birds

Watch videos I’ve filmed of a variety of colorful and entertaining birds on my blog post, Neotropical Birds.