If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to be a field biologist, you may enjoy this story I wrote about my time spent assisting with an endangered bird survey conducted in the Sierra Nevada mountains of northern California. Near the Summer Solstice, I joined a team of field ornithologists conducting a survey of the Willow Flycatcher, a small songbird whose numbers have plummeted in the southwestern portion of its range. But the restoration of its willowy wetlands is improving its chances for survival and the biologists are busy documenting its response.

This story is a lighthearted take on the joys and tribulations of living and working in the field; sleeping in a tent, cooking over a fire, and rising before dawn. The setting is gorgeous, with alpine meadows surrounded by pine forests, where the stars are bright and the nights are crisp. I’m feeling just a little guilty that you couldn’t be there with me, so I’m sharing my experiences with you through the lens of my field journal entries below.

Conducting Research in California’s High Sierra

It’s 4 am and the birds are already awake. Not me, the full moon shone too brightly in my tent last night and it didn’t set ’til right before the alarm buzzed. This ain’t no sleepin-in-half-the-day vacation. We’re here on serious business: counting birds. And birds, as I’m reminded right now, so snug in my sleeping bag, get up waaaay too early. And those Wilson’s snipes never did quiet down, winnowing the night away over the meadow with their incessant courtship displays.

There’s dew on the tent and the air is nippy, despite the fact that it’s almost summer solstice, but at 7,000 feet elevation, that hardly matters. Good thing I slept with my field clothes tucked into the bottom of my sleeping bag to keep them (and my feet) warm. I yawn, take a big stretch, pull the headlamp on over my beanie, and step out of my tent. The dawn chorus is going strong; nuthatch, finch, robin, warbler, vireo all singing their hearts out. Coyote yip in the distance.

It’s not morning without coffee so I fire up the Whisperlight and brew a strong batch, complete with my comfort food essentials — mini marshmallows and ground chocolate! I pour myself a big cuppa joe and sit down at the fire circle, smoke still rising from the embers, which I stir with a stick, awakening a tiny flame, and I warm my chilly hands.

My field partners are ready and so we head out, shouldering our day packs laden with field equipment and make our way down the trail, the path illuminated by our headlamps. There’s a crunching sound as our boots strike the frosty ground. Hiking through a lodgepole pine forest, branches snap as we navigate a maze of downed trees. We stop to study the topo map and make a course correction aiming north towards our destination.

6 am — Reaching our first survey site daybreak is finally upon us and I can see a heavy mist hanging over a large meadow that’s the size of several football fields. The scent of mint fills the air as I walk through a patch of pennyroyal, releasing its aromatic oils.

This is a typical alpine meadow, covered in grasses, sedges, and rushes, each preferring a different degree of moisture which clues us in to just how soggy a certain area might be. So, as I take my first steps into the chilly creek water, I am grateful for the hip waders that are keeping me warm and dry.

My field partner, Kristen Strohm Hein, listening carefully for the songs of birds

Our research protocol dictates that we crisscross the meadow, stopping every 100 meters to look, listen and record the birdlife we see and hear. Each song is subtle but unique; the squeak of a grosbeak, the warbling of a vireo, the chipping of the nuthatch, the quick three beers of the olive-sided flycatcher. Check, check, check and check. A noisy pair of sapsuckers catches our attention and we see them visiting their nest cavity high in a cottonwood and hear the incessant begging of their hungry nestlings. Check.

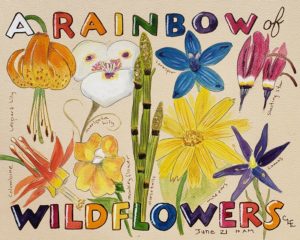

8 am— The sun finally peeks over the ridge to our east, burning off the morning mist revealing a vast field of wildflowers of every color. White corn lily, wild onion, mariposa lilies; yellow monkeyflower, buttercup, mule ears; orange lily; red paintbrush, columbine, elephant head; pink pussy paw; blue larkspur; purple camas, penstemon, lupine, shooting stars. I pick a blossom and press it between the pages of this journal.

Wildflower painting by Christine Elder

10 am — It’s warming up, so off with the layers –knit beenie, neck gaiter, wool sweater, gloves, all stuffed in the daypack and traded for a snack — my leftover steak sandwich from last night’s BBQ and a gulp from my still warm thermos of coffee.

I come across the sun-bleached skull of a cow, and follow the trail of its skeleton down the creek bed — a scapula here, a femur there, vertebrae, ribs, sacrum, hip — perhaps carried by the spring snowmelt. Glad we haven’t run across any live ones; they do a fine job of stomping on all the wildflowers but who am I to judge, as a hypocritical carnivore?

I trade surveying duties with my partner and find a dry spot in the meadow to take a little cat nap while my team carries on, catching up on last night’s sleep. I watch the swallows and dragonflies circling above, then closing my eyes, I place my cap over my face for shade. Suddenly without the distraction of vision, my senses of hearing and smell become heightened and I hear the gurgling of the creek and smell the pungent scent of sage. The distant rumble of logging trucks jolts me back to reality and reminds me that this isn’t a utopian paradise.

Catching up with my team at the other end of the meadow I pass evidence of beavers. An industrious family has engineered a small dam across the stream and a lodge sits in the middle. A well-worn path with cut willow saplings along its edge leads to the stream. The beavers are valued here for the work they do in slowing and deepening the water, which also improves the habitat for the willow and the birdlife that finds shelter and nest sites in its dense branches.

Noon —Finally we hear the unmistakable ritz-bew of our most highly prized quarry — the willow flycatcher -and spot him singing from the top of the tallest willow. This is a very good sign. He’s an indicator species for a healthy ecosystem and demonstrates by his presence the success of the multi-year restoration project that has improved this wet meadow habitat for not only the flycatcher but for all the wildlife…the beaver, the fish, the frogs, and the wetland wildflowers. We smile and give each other high fives. He’s one of just 100 pairs that are thought to remain in the entire Sierra so there’s still a long way to go but it’s a good start.

2 pm — Our work done for the day, we leave the meadow and head back to our camp through the forest. The air is hot and dusty now; I can feel its dryness in the membranes of my nostrils. Sweat drips from my forehead, stinging my eyes. Funny how the heat of the day brings out different smells than that of the moist morning air.

So when I pass a big Jeffrey pine, it’s a ritual of mine to wrap my arms around it, close my eyes, and inhale deeply, taking a big whiff of its bark, which warmed by the afternoon sun gives off the unmistakable scent of rich butterscotch.

Still sweating from the midday heat, I’m ecstatic when we come across a creek. Kneeling down at its edge, I cup my hands, dipping them into the welcoming water and splash its chilly snow melted goodness over my face. What the heck, I just dunk my whole head in, getting goosebumps from the sensation, then just as quickly I flip my head up; water droplets arcing into the sky. Lastly, for good measure, I wet my handkerchief and tie it around my neck to keep me cool for the remainder of the hike.

4 pm –Finally arriving back at camp, I head straight for the cooler sitting under the picnic table and pull out a much deserved hard cider; an indigenous beverage first enjoyed in the 1850s by the local gold miners who made it from their apple orchards.

We each fall gratefully into our camp chairs. I unlace my dusty boots and feel the refreshing air on my cramped toes. I flex and circle each ankle then prop my poor dogs up on a fire circle rock. I’m thankful for the shade of the quaking aspens, for my tender, sunburned cheeks are a sharp reminder that I forgot to apply sunscreen in the predawn rush.

From our comfortable vantage point, we can see the edge of the meadow, and we watch the wildlife as if it’s a TV show, rapt and silent. A golden eagle gets chased by two territorial red-winged blackbirds, a pair of honking sandhill cranes takes a loop of the meadow before landing. Golden-mantled ground squirrels chase each other over logs and around boulders. And the show goes on ’til dusk. No commercials!

6 pm —Dinner is a medley from our individual food stashes — couscous, sautéed green beans, instant mashed potatoes. Forgot the s’mores, how on earth did I do that! Will I be forgiven? Thankfully we’re all too beat to care. Before long the full moon is rising and it’s easy to see without headlamps. I walk to the edge of the meadow and watch the moon peek over the granite cliffs that border its eastern edge. High, wispy cirrus clouds pass lazily in front of the moon, changing its light, and I can hear again the ethereal sound of the winnowing snipes. A couple of males, at opposite ends of the meadow, vie for the attention of their potential mates. They bring up a memory from my youth that happened not far from here at a summer camp where I went on a proverbial snipe hunt and was left holding the bag while my ‘friends’ ran off back to camp! I didn’t realize that snipes were real birds until I became an adult!

9 pm — We gather ‘round the campfire and soon become mesmerized by the dancing of the flames and the ember’s glow, a ritual deeply ingrained in our DNA ever since humankind’s ancestors tamed fire more than a million years ago. As the embers die down, we reluctantly snap out of our meditative state and raise our weary bones to head for our tents, for it won’t be long ’til the songbirds awaken us again with their early morning reveille. Another day has come and gone too soon in the high Sierra.