World Migratory Bird Day

World Migratory Bird Day is an annual awareness-raising campaign highlighting the need for the conservation of migratory birds and their habitats. It is celebrated twice each year, at the height of the migratory seasons, on the second Saturday of May and October

In the Western Hemisphere, more than one billion birds and over 200 species migrate in the spring and fall, traveling either north and south in latitude or upslope and downslope in elevation to access the best resources, especially the most abundant food.

I’ve been fortunate to observe many of these species in migration, from Arctic Terns in Alaska to Franklin’s Gulls in Peru. So, I thought I’d share what I’ve learned about bird migration with you!

In the Eastern Hemisphere, bird migration flyways also include routes flying east and west, as birds nesting in Europe and northern Asia travel to Africa, southern Asia, and Australia for the northern winters. Birds migrate for the same reasons that some other types of animals do, from mammals like the African wildebeest and Pacific grey whale, to fish such as salmon and steelhead trout, to insects like the iconic monarch butterfly.

For example, the pectoral sandpiper is a small, migratory wader that breeds in North America and Asia, wintering in South America and Oceania. I was lucky to see it in it’s summering grounds in Barrow, Alaska.

Why Birds Migrate In Spring

For birds migrating north in the northern spring, the reasons are the same, as this season is autumn in the Southern Hemisphere. Even for birds who spend the northern winters in tropical areas that lack a cold winter at any time of year, the abundance of insects, seeds, berries, and nectar still fluctuates between wet and dry seasons, and the migrants have to compete for food with the year-round tropical residents. While food supplies are adequate to support this competition between adults, the northern summers provide a greater abundance with less competition to support the awesome task of laying eggs and raising young. Most songbird parents have to hunt, catch, and carry more food to their nestlings at least every 5-10 minutes!

Longer daylight hours in the northern and southern summers also help birds to gather more food each day, and spring in both hemispheres provides optimal amounts of sun and water for plant growth for more bird food, habitat for nesting, and concealment from predators. Birds who migrate to higher elevations do so for similar reasons as their cousins who migrate to northern latitudes, to raise their young among the abundance of food available in montane habitats in the spring and summer months.

Why Birds Migrate In Autumn

Although most folks in the Northern Hemisphere believe the reason birds migrate south (or downslope) in the fall is to escape the winter’s cold, that is only partially true. With their custom-fit down jackets and many other adaptations to survive cold temperatures, even the tiniest migratory birds can usually survive a freezing spring or autumn storm, although it does require more energy (and thus food) to do so. The insects that most birds eat, however, are dormant during cold northern winters, and seeds, berries, and flower nectar are harder to find under the snow, forcing the birds to take a culinary vacation for food.

This is also true for some raptors (hawks, eagles, falcons, and owls) who live where their small mammal prey hibernate through the winter and where most smaller birds that could be prey are also unavailable due to their own migrations. Some small raptors such as American kestrels, Falco sparverius, and flammulated owls, Psiloscops flammeolus, also depend upon large flying insects that are dormant in freezing temperatures, such as grasshoppers and moths.

Which Bird Migrates the Farthest?

The longest migration of any bird in the world is flown by the Arctic tern, Sterna paradisaea, who nests in the high Arctic regions of Europe, Asia, and North America. This delicate seabird flies 44,000 miles (70,800 km) round trip each year to spend the northern winter (southern summer) in the southern tip of South America and even as far south as Antarctica!

***Learn more about Arctic Terns on my other blog post HERE***

How Birds Find Their Way

How do birds accomplish this amazing feat of migration and find their way back to their nesting and wintering grounds each year? Research has shown that birds use many simultaneous clues to navigate by, including the orientation of the stars, the direction of the sun, the path of the wind, the forces of the Earth’s magnetic field, visual topography and landmarks, by following their parents and/or other members of their species, and in some cases, even their sense of smell. None of these clues are perfect, however, nor are they always available.

On overcast days and nights, for example, birds may not be able to see the sun and stars, and scientists tracking migrating birds with radar have seen them frequently flying in the wrong direction when navigating by the wind’s direction on starless nights. Often these birds can right their courses later, but each detour requires additional energy reserves and exposes them to additional dangers such as starvation, predation, or collision with transmission lines or other human-made obstacles. Despite their navigational superpowers, some birds do get lost along the way, providing birdwatchers with occasional opportunities to see vagrant individuals thousands of miles and whole continents away from their usual homes.

Why Some Species Don’t Migrate

Of course, not all birds migrate. What enables those that don’t migrate to stay in one region all year long and avoid the perils of migration? Again, it’s all (or mostly) about the food. Wrentits, Chamaea fasciata, for example, are loyal homebodies who choose their lifelong mates when only 30-40 days old and rarely travel more than ¼ mile (4/10 km) from their birthplace their entire lives. Residents of low-elevation, coastal and foothill shrublands in western North America, their temperate winters supply all the food they need, with berries supplementing their diet when fewer insects abound.

Other birds whose food is less available in winter work diligently when food is abundant to store caches of food that they can eat later, thus avoiding the need to migrate. For example, a single Clark’s nutcracker, Nucifraga columbiana, may store more than 30,000 pine seeds in the ground in a single summer, plenty enough to feed on through the winter and for many more to grow into young pines the following spring.

Scientists have even discovered boreal owls, Aegolius funereus, a species who resides year-round in the highest latitude and highest elevation forests of North America, storing frozen prey that they later sit on to warm before eating, almost as if they were incubating an egg! Birds that depend on cached winter food stores are particularly vulnerable to climate change, however.

Recent studies of the quiet-winged, smoke-colored Canada jay Perisoreus canadensis, have shown that many of their winter food stores in recent years have spoiled during warm spells and that some unspoiled caches have still lost some of their nutritive value through repeated freeze-thaw cycles in a season.

Woodpeckers, nuthatches, and creepers need not migrate because they eat insects living inside the bark and wood of trees, which unlike flying insect prey, is available all year long. One exception to this woodpecker rule is the beautiful, pink-bellied Lewis’ woodpecker, Melanerpes lewis, who eats a combination of wood insects that are available year-round and flying insects that are dormant in winter.

After nesting in the montane pine forests of western North America, the Lewis’s woodpecker makes a short-distance migration downslope to foothill oak woodlands, riverside cottonwood groves amid low-elevation grasslands, and similar habitats where both food types remain available throughout the winter, and then returns to its nesting forests in spring, after flying insects have hatched and become abundant once again.

The High Cost of Migration

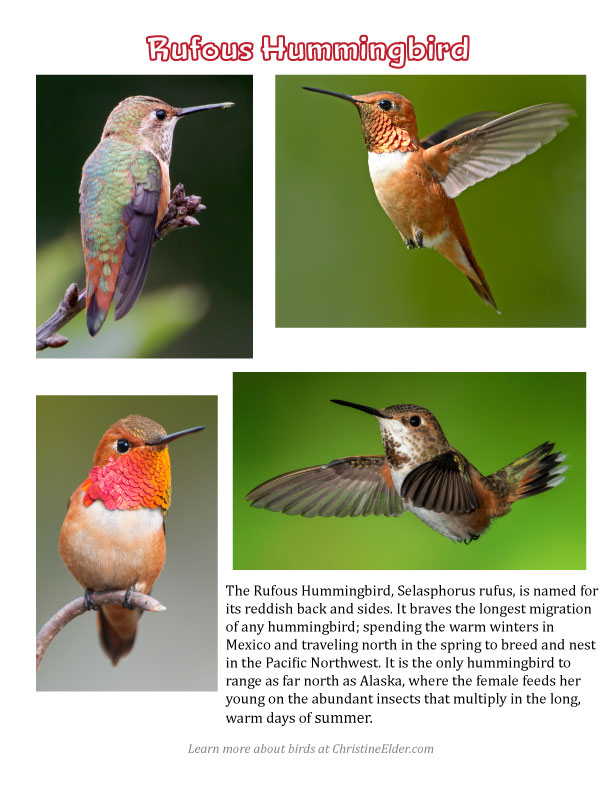

Although the culinary rewards of migration are substantial for the species that do undertake this feat, the journey does come at quite a cost. Consider for example the rufous hummingbird, Selasphorus rufus. This fairy-sized bird has a wingspan of just four inches and weighs only as much as two US pennies, yet flies over 6,000 miles (9,650 km) round trip each year on those tiny wings! Many songbirds lose between ¼ and ½ of their body weight during this heroic journey.

This underscores the critical importance of protecting “rest stop” habitat for migrants in which they can briefly rest and feed before continuing their migration. Many researchers and conservation organizations are working to map migration routes of both common and endangered birds in efforts to identify and protect the most important “stopover” sites to help migrating birds survive. They have found that birds follow distinct “flyways,” bird “highways” and migratory corridors that follow geographic patterns of more consistently favorable winds and more predictable food and shelter.

For example, in the Goshute Mountains between the US states of Nevada and Utah, more than 1,200 raptors can be seen overhead in a single day of peak fall migration as hawks, eagles and falcons from a vast area to the north funnel in to take advantage of the updrafts of wind rising up the mountainsides, and to avoid the Great Salt Desert in which food and shelter are scarce. Similarly, in Veracruz, Mexico, a “River of Raptors” hosts even larger numbers of daily fall migrants funneling in to avoid flying over the Gulf of Mexico. Protecting migratory hotspots like these is essential for the conservation of the bird species who need them.

Other bird species who do migrate over the Gulf of Mexico must fly non-stop for between 15-30 hours over 600 miles (965 km) to do so, and require the protection of stopover habitats with abundant food, few threats, and diverse forms of shelter on both sides of the water. This is similarly true for birds flying over or around the Great Lakes between Canada and the US, and other large bodies of water and similarly-avoided large deserts.

You can help protect these important migration flyways and rest stops by donating to conservation and research organizations, such as the national and global groups linked at the bottom of this post, and/or to local land trusts conserving natural areas near your home.

Read on for some additional ways you can help migrating birds!

How You Can Help Migrating Birds

There are many ways you can help the 100’s of species of birds and millions of individual birds that migrate north in the spring and south in the autumn. Here are some ideas.

Attend an Event

- Attend or organize an event near you to celebrate World Migratory Bird Day. You can find hundreds of events throughout the globe at this link: http://www.worldmigratorybirdday.org/events-map.

Protect Birds: Be the Solution to Plastic Pollution

- Learn about and act on the 2019 conservation theme of World Migratory Bird Day: “Protect Birds: Be the Solution to Plastic Pollution.” An estimated 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic has been produced in the past 65 years, and plastic has become a significant threat to birds across the globe. 91% of plastic is not recycled but rather discarded as waste, accumulating in landfills and the natural environment, and leaching toxic chemicals like biphenyl. When plastic items break down into tiny pieces, seabirds and other wildlife accidentally scoop them up with their prey. A recent study showed that for several seabird species, 80-90% of individuals have ingested plastic. Another recent study showed that for the majestic and elegant Laysan albatross, Phoebastria immutabilis, 40% of chicks die before leaving the nest, with stomachs filled with plastic.

- You can be a part of the solution! Bring reusable bags when shopping at grocery and retail stores, and if you forget (who hasn’t?), ask for a paper bag instead. Many small groceries now also provide a stack of empty cardboard boxes leftover from their deliveries that make a great bag replacement. Bring a reusable thermos, cup or bottle to work and play, to refill with water, coffee, or other drinks throughout the day. Think twice before purchasing items packaged in unrecyclable plastic. Purchase fresh bread sold in paper bags instead of plastic bags. Buy larger containers (to the extent that you won’t waste contents) of yogurt and other goods instead of multiple individual serving containers to reduce the total amount of plastic used.

- Seek out stores and co-ops near you that stock bulk supplies of shampoos and other products that are primarily sold in plastic, so you can bring in reusable containers for a refill instead of buying new plastic packaging. If you buy soda, beer or other beverages packaged in six-packs, cut the plastic six-pack rings before disposing of them in the trash. I have personally seen gulls with a foot or head trapped in one of these rings.

- Think twice before purchasing mylar balloons – can flowers, paper streamers, fabric buntings, or other more earth-friendly decorations bring the same amount of joy to your festivities? If you fish, take the extra time to find and remove as much broken fishing line as possible, as I have also seen gulls tangled in these lines. Pick up litter when you see it, and join or organize a community clean-up event near you.

Invite Wildlife into Your Garden

- Create a wildlife-friendly garden with native plants, water sources, and cover. The Nature Conservancy and Cornell Lab of Ornithology have provided a wealth of information to help you design a fabulous bird-friendly garden.

Create Bird-friendly Windows

- Modify your windows or apply inexpensive UV window decals to prevent birds from crashing into your windows. Window strikes are one of the three leading human-induced causes of bird mortality, along with habitat loss and hunting by cats, and millions of birds are killed by window collisions every year.

- To learn more about how to make your windows bird-safe, visit The American Bird Conservancy, buy bird-deterring window decals, or check out this homeowner’s guide for surefire ways to make windows friendly to birds.

- Learn more about protecting birds from window strikes.

Feed Your Feathered Friends

- Provide bird feeders stocked with suet, seeds, nectar and dried insects to attract native birds. To keep your feeder birds healthy, be sure to clean seed feeders and the ground beneath them every one to two weeks and clean your hummingbird feeders every three to five days. Follow the cleaning instructions provided by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. If you see a sick bird at your feeder, take the feeder down for a week to reduce the spread of disease.

Ban Cats From Your Yard

- Prevent cats from entering your garden and killing birds. Over one billion birds are killed by domestic and feral cats each year in the US, plus 200 million in Canada, 365 million in Australia, 55 million in the UK, etc. In locations where threatened or endangered bird species are present, mortality caused by cats is especially important to prevent.

Support Bird Conservation

- Support bird conservation organizations like those listed below as well as local and global land trusts and other conservation organizations in your area that help protect birds and the habitats and ecosystems upon which they depend.

Fight Climate Change

- Join the fight against climate change, which in some cases has already been shown to affect the timing of bird migration relative to the emergence and growth of their insect and plant food sources, and which contributes to storm patterns that may affect birds while on their migration journey. Vote! Write to and call your elected representatives and leaders of the companies whose goods you buy.

- Reduce your own carbon footprint to the extent possible by carefully selecting the miles you drive, electing clean energy options for your home to the extent they are locally available, eating locally-grown foods that require fewer fossil fuels to be transported to your door, carefully selecting the other goods you buy, carpooling or using public transportation when possible, grouping errands to reduce driving and increase your time efficiency too, considering fuel economy when purchasing a new vehicle, and be creative with additional ways to help. Spread the word to friends and family, as well as throughout your community by writing letters to the editor and engaging in community events.

See more resources at the end of this post for more ideas on helping migratory birds in your area.

Three Migratory Birds of the Americas

Read on about three species of migratory birds of the Americas (which happen to migrate through my area of Oregon); the Black-headed Grosbeak, Wilson’s Warbler and Rufous Hummingbird. Feel free to download the handouts below which include high-resolution photos and more information about each species.

Black-headed Grosbeak

Black-headed Grosbeaks, Pheucticus melanocephalus, spend winters in Mexico and migrate to the western half of the U.S. and southwestern Canada in spring to raise their young. Their strong bill helps them to crack thick seeds and crush hard-bodied beetles and snails. They also dine on monarch butterflies, whose toxins make them poisonous and inedible to most other bird species.

Check out this great video of mom and pop grosbeaks feeding their young!

Rufous Hummingbird

The Rufous Hummingbird, Selasphorus rufus, is named for its reddish back and sides. It braves the longest migration of any hummingbird; spending the warm winters in Mexico and traveling north in the spring to breed and nest in the Pacific Northwest. It is the only hummingbird to range as far as Alaska, where the female feeds her young on the abundant insects that multiply in the long, warm days of summer.

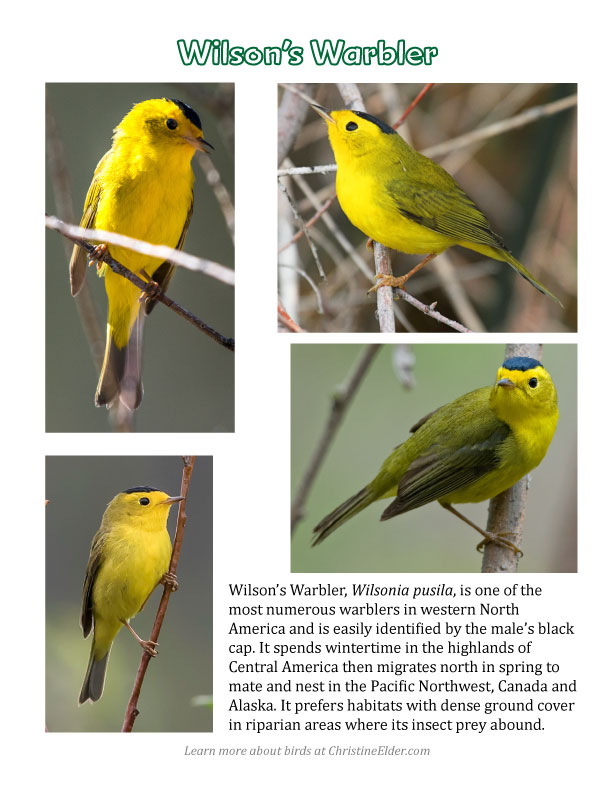

Wilson’s Warbler

Wilson’s Warbler, Wilsonia pusila, is one of the most numerous warblers in western North America and is easily identified by the male’s black cap. It spends wintertime in the highlands of Central America then migrates north in spring to mate and nest in the western United States and across Canada from coast to coast. It prefers habitats with dense ground cover in riparian areas where its insect prey abound.

Tips for Identifying Migratory Warblers in Spring

There are 30+ species of wood-warblers that migrate from Central America through North America on their way to their summer breeding grounds. So I wrote a warbler identification guide to help you to identify these species.

Learn More about Migratory Birds

-

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology website.

- Partners in Flight website.

- World Migratory Bird Day website.

- American Bird Conservancy website.

- National Wildlife Federation website.

- National Audubon Society website.

- American Birding Association website.

- Royal Society for the Protection of Birds website.

- Book: A Season on the Wind; Inside the world of spring migration. By Kenn Kaufman.

- Simple Solutions for Protecting Birds from Windows.

Related Bird Resources on this Website

Here are some more stories, videos, and bird sketching resources I’ve written to keep you inspired about birds.

My Costa Rica Birding Big (sketching) Day

Identifying Warblers in the Spring

A Black-headed Grosbeak Nest (video)

Blue-winged Warbler

Did You Enjoy This Story?

If you’ve found value in this story and believe in my mission to educate youth and adults alike on the value of nature, I invite you to make a donation to help broaden and deepen the work I can accomplish.

Click the Paypal ‘Donate’ button below to donate any amount you wish to support the conservation and education work I do. You don’t need to have a Paypal account to donate, you may also choose to use a credit card, or simply send put a check in the mailbox if you wish. Thank you!